What is out there already?

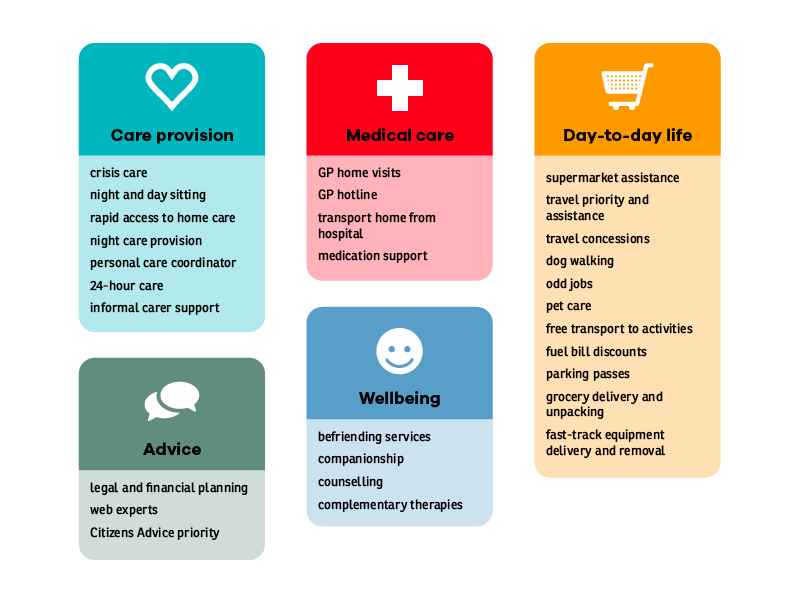

In our user research, we discovered existing entitlements that people can access in the last phases of life.

Terminally ill patients aged under 65 are entitled to fast-tracked financial support through the Department for Work and Pensions. There are also other practical measures available - from occupational therapists doing speedy deliveries on equipment needed in someone’s home, to the automatic allocation of double GP appointments, through to a Gold Card in Airedale which signifies to health and care professionals that the person is in their last phase of life and might need slightly different treatment.

It became clear as we met more practitioners, from specialist palliative care nurses to physiotherapists, that each profession and region had a set of entitlements available to those in the last phases of life.

We asked practitioners to complete a survey shared on Twitter and by email to professional groups to help understand more about what is available and how information on entitlements is shared at the moment. Thirty respondents told us there was no single place to find out about what patients have the right to receive. Practitioners mentioned that information was ‘ad hoc’ or ‘by chance’ or available through a ‘maze’ of websites.We would like to see a clearer way for people to discover this information. A practical solution would be to develop a web page in partnership with Citizens Advice to help people find what they need from an already trusted source.

Our survey respondents also gave us some ideas about other services which might be helpful, such as free laundry services, night sitting and priority access to care and support.

As well as hearing from practitioners, patients told us about some of the difficulties they encountered and where they would like support to overcome them. It became clear that many people at end of life feel that they are a burden to the health service, to their carers and to their families.

We heard stories about people leaving hospitals after waiting a while because they felt burdensome, only to find that they were unable to make another appointment for over a week by which point their condition had worsened.

They also highlighted the problem of social exclusion.

I can’t do the things I used to love to do... swim, motorbiking... so apart from reading I can’t do anything. Anything to do with being physical. Life gets very enclosed, very narrowed down. It is hard to stay positive when you feel everything is shrinking around you.

And told us how it’s easy to fall into a vicious cycle once getting out and about becomes difficult.

You have to motivate yourself to get up every day. The more you sit and do nothing, the more you sit and do nothing.

What other models have people been thinking about?

We did some desk research on emerging models for supporting and caring for people at the end of their lives within communities.

Reports from the National Council of Palliative Care and Nesta (PDF) map out ways in which communities can and are stepping up to help and how the role of social movements is increasing participation in informal health systems.

This shift - from formal to informal, where local communities come together to make changes in their care and their lives, is going to be vital in helping sustain the NHS.

... the NHS can’t do it alone. Because the NHS isn’t just a care and repair service, it’s a social movement. We’re going to need active support from patients, the public, and politicians of all parties.

Practitioners told us they want to find ways to break down the isolation end-of-life patients encounter. They think this could be helped by engaging the community more in healthcare.

Hospices and other organisations, the broader health and social care sector, need to really think about how to support carers, and the public to enable people to live and die well, and to cope in their grief. I think we’ve made it very much a professional problem, but actually, the solution lies in empowering patients, families, and carers, and the general public, their networks, and their communities to do a lot of the help and support themselves.

Continuing our research

After starting to prototype our ideas we discussed them with a group of practitioners and commissioners from Lincolnshire who identified a number of priorities they would want to address through the system:

- Identification of people - how to find the people who need support and make sure they have access to services and the things they might need.

- Communication - how to talk about living with a life-limiting condition, especially as people are coming towards the end of life. How can people communicate about their needs? How can difficult conversations happen?

- Social isolation - how can people feel less isolated when they are living with a life-limiting condition?

They started to list some of the organisations they could involve in developing a system and some of the practical ways that support could be offered, from help putting out the bins to a trip to the hairdresser. Read more about the Lincolnshire workshop.

We would like to see communities take our ideas for a new model of entitlement system on board and put them into practice.

If you are interested in taking part please get in touch with us at [email protected].