A service that puts people at the centre of their medical information by giving patients, carers and clinicians the right information at the right time.

We have developed demonstration prototypes and a set of recommended next steps, based on our research into how technology can improve care for older people at the end of life.

Why?

Communication is an important part of care. Sharing useful, accurate information will make it easier for patients and their carers to manage their own lives and easier for clinicians and professional carers to deliver care.

The typical experience of an older person with multiple long-term conditions exemplifies many problems familiar to other users of the NHS; they are “super users” of the system, so creating services that work for them will make it easier to make robust and scalable services that work for everyone.

The 2008 End of Life Care Strategy stressed the importance of people dying in their preferred place; this has led to a number of tools and applications that support this, but this is not the only way technology can be useful. As Actions for End of Life Care 2014-16 (PDF) sets out, there is more to the last phases of life than choosing a preferred place of death: “We now need to ensure that living and dying well is the focus of end of life care, wherever it occurs.”

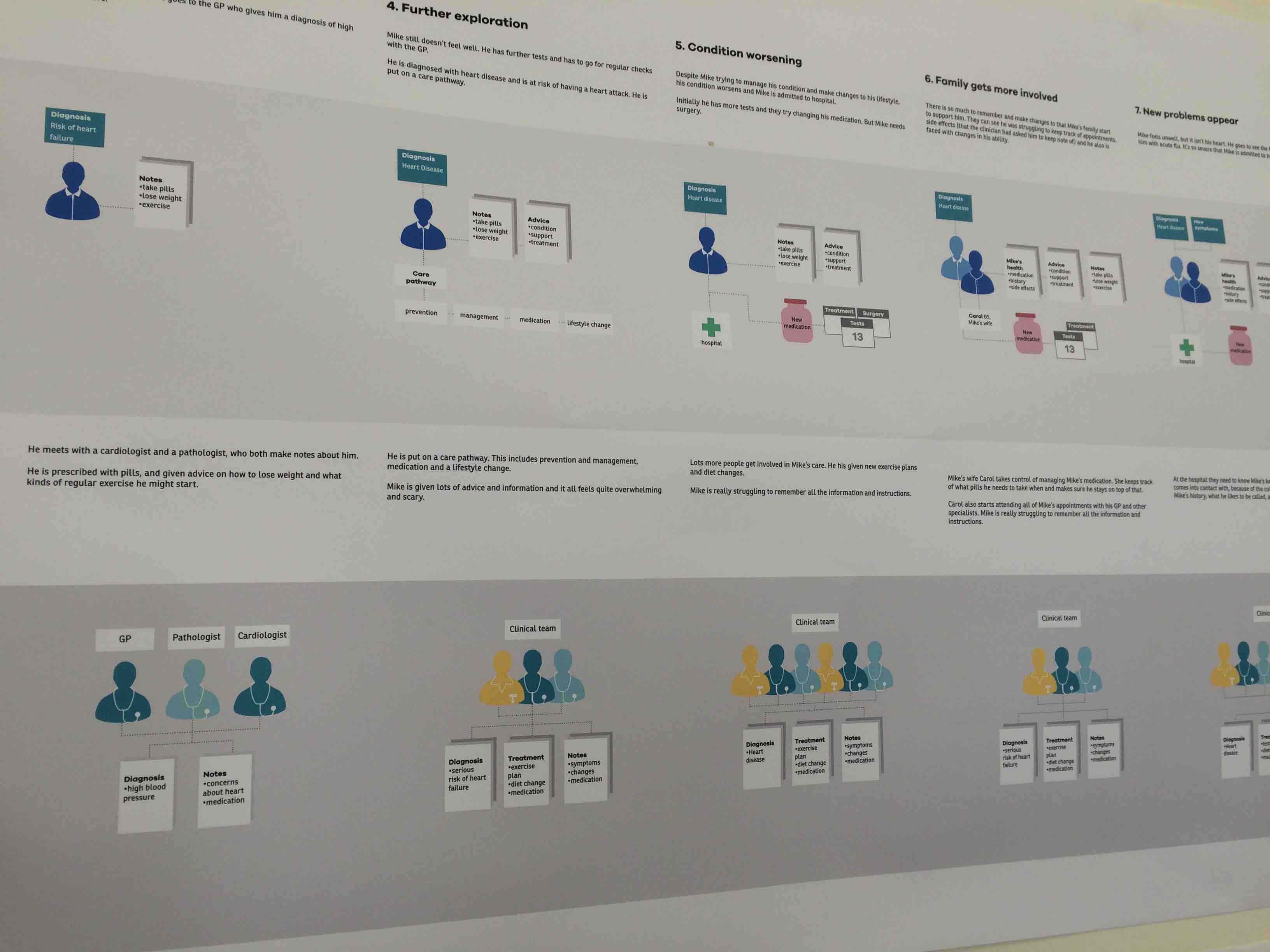

A person with, for instance, congestive heart failure and Type 2 diabetes will be in the care of several specialist teams, in different organisations. Our research has shown that helping people to navigate the complexity of their care across many teams and organisations, and be sure their voice has been heard, are important for improving quality of life for both patients and carers.

Full Report User research: patents, carers and clinicians in end-of-life careI often think there is a mismatch between what people have heard and what I have said. I have started to ask to see what they document now.

I panic when I am listening and then I don't hear it all, so I need a better way to record conversations or make sure I remember to have someone with me.

What we learnt

Useful technology is person-centred. Many existing technology products and services are aimed at managing a single condition in a single setting; as a person becomes more unwell, this means they are expected to use a tool for their diabetes, another for their rheumatism, another to monitor their general wellbeing, another to book an appointment at their GP, or another to organise transport. Organising technology around patients rather than systems or organisations will make it easier to grow and manage it over time.

There’s a lot of living at the end of life: the last phases of life could last for years or months, and should not be dominated by admin tasks to support healthcare. And a person’s engagement with their care should not be limited to expressing their preferred place of death or attitude to resuscitation.

Everyone should be able to understand and access important information about their health and care. This information should be up-to-date, accurate, and organised around the patient - not the organisation or team delivering the care.

It’s important that carers and clinicians know how people want to be treated. For patients at the end of life, “preferences” are often interpreted as information about a person’s preferred place of death or their approach to resuscitation, but they aren’t the only important things. It’s important that patients can feel comfortable, express their priorities and share their expertise in their own conditions.

People with multiple long-term conditions may be in the care of several organisations and many different clinical teams; it’s not unusual for one person to have an extended care team of more than 30 people. This is time-consuming for everyone: for patients and carers who repeat their medical histories several times a day and spend hours on the phone chasing appointments, and for clinicians who need accurate, up-to-date information. Giving everyone involved the right information at the right time would give patients and carers more time to live, and clinical teams more time to care.

The NHS recognises the importance of people being able to access and add information to their medical records (as outlined in the Five Year Forward View) but there is not yet clear best practice about how to implement this. It is important that information flows as needed between the patient, carer and their clinical teams without becoming a separate messaging system; that information is stored securely and that patients understand who is using it, and why; and that data is not tethered to a single device or system.

What we have done

Research

Full report Research findings

Our research activities have included qualitative research, technology discovery, desk research and expert review.

We started by speaking to patients and clinicians to understand their needs, and then undertook an investigation into existing technology provision to see how those needs were being currently met, with what infrastructure and by which products and tools, including electronic palliative care coordination systems (EPaCCS), care plans, preference tools, one-page profiles and Do Not Attempt CPR (DNACPR) forms, and the gaps in current provision.

This was supported by desk research to understand current thinking and best practice, and the wider vision as outlined in the Five Year Forward View and Personalised Health and Care 2020.

Service design

Full report Service design

We mapped the experience and the information flows from as many perspectives as possible and focussed on understanding the most difficult parts of the experience: the moments of complexity, communication and collaboration.

We also looked at the beginning and end of the patient experience, how people would begin and end their engagement with the service, and understood accessibility needs of different service users.

See the service design report.

Prototyping

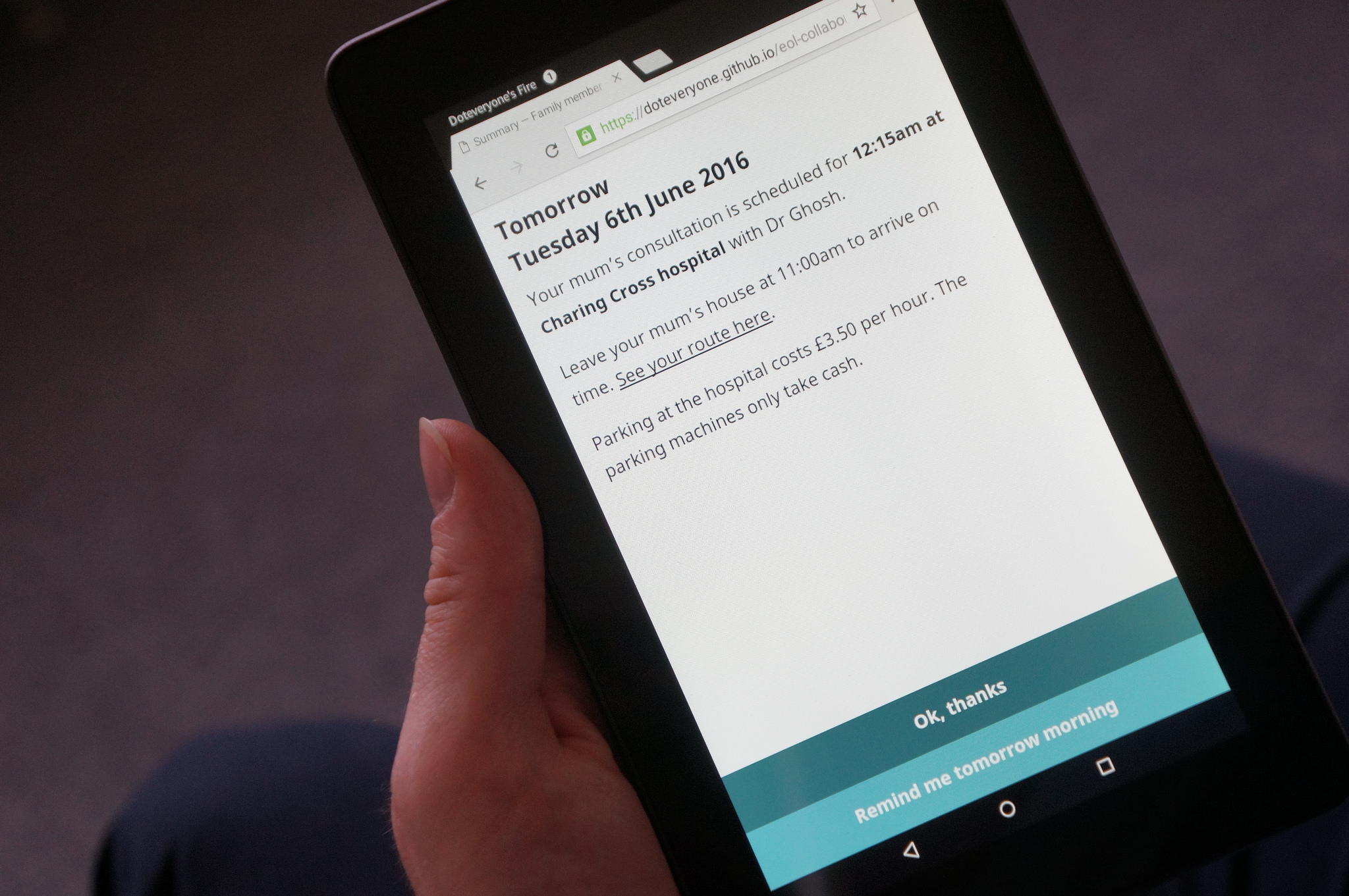

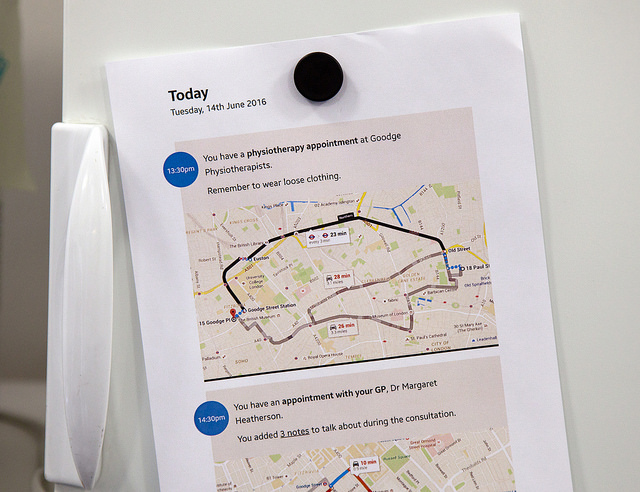

Full report PrototypingWe made HTML prototypes to bring to life some of the most important moments in the experience map, demonstrating how permissions would work and how the same information could be used in different contexts, for patients, carers, transport staff.

The prototypes also show how design, language, level of detail would change for different people at different times, making it clear that this is not a single product, but a service that relies on flexible infrastructure and clear data-sharing guidelines.

We investigated how different ways of communicating (for instance, using voice or text) would change interactions and be useful for different kinds of users at different times.